Today’s

post is on two philosophical paradoxes of God’s existence: one that proves it,

and one that disproves it. The first

paradox is called The Ontological Argument. . .

St.

Anselm was an 11th century philosopher who used logic and reasoning

to prove God’s existence. He invented The

Ontological Argument, which is a dialogue between him and a character named

“The Fool”. The Fool is an atheist who

understands the concept of God, but doesn’t believe that God actually exists.

The

argument is based off of two givens: that God is “the being of which nothing

greater can be thought” and that existence in reality is superior to existence

in the mind.

The

Ontological Argument:

Anselm:

If

God existed he would be the greatest thing

that

could possibly be—“the being of which

nothing greater could ever be thought”, correct?

The Fool:

Yes.

Anselm:

And

the concept of God exists in

your

mind, correct?

The Fool:

Yes, He exists in my mind, not in reality.

Anselm:

But

which is greater: something that exists in

reality,

or something that exists solely in your mind?

The Fool:

Something that exists in reality is greater than

something that exists solely in my imagination.

Anselm:

So

“the being of which nothing greater can

be thought” would be

greater if it existed in reality,

and not just in your mind, correct?

Fool:

Yes.

Anselm:

But

the being of which nothing greater can be

thought

cannot be greater than it already is!

That

would

contradict its very nature as “the being of

which

nothing greater can be thought”!

Therefore,

God

exists not only in your mind but in reality as well.

Yikes,

that was a lot to take in. . .

So

let’s break it down. Here is what we

need to know:

1. That God is the being of which nothing greater

can be thought, meaning that we can’t possibly think of anything greater

than God. He’s it. He’s just the best.

2. According to

The Fool, God exists in the mind, but

not in reality, meaning that though we may believe in God, he merely exists

in our imaginations and not in the real world.

3. Both Anselm

and The Fool agree that an object that

exists in both the mind and reality is greater than an object that exists solely

in the mind.

The

conclusion of these three statements: God

would be greater if he existed in both realms, as opposed to solely the realm

of thought.

The

Fool agrees with the three numbered statements and ultimately the underlined

fourth statement, but not all statements can be true at once.

If

1 and 2 are true, then 3 can’t

be true.

If

2 and 3 are true, then 1 can’t

be true.

If

1 and 3 are true, then 2 can’t

be true.

No

matter how you look at it, the statements cannot all be true at the same time,

rendering the Fool’s argument invalid, and therefore proving God’s existence.

And

now for Epicurus’ argument. . .

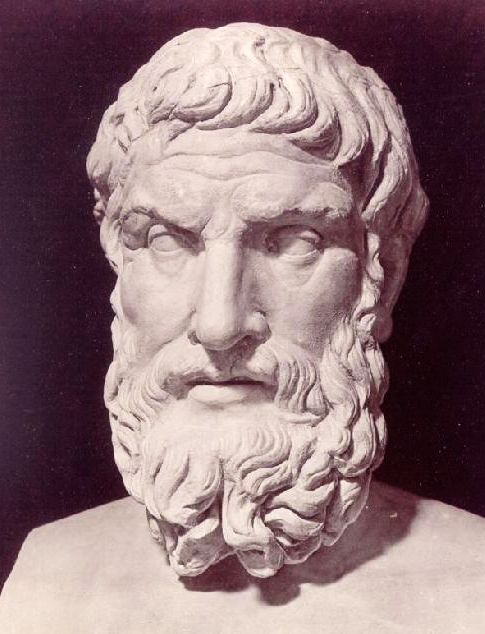

Epicurus

was an ancient Greek philosopher who, like Anselm, was interested in the

concept of God. However, Epicurus used

logic and reason to disprove God’s

existence. . .

Epicurus’

Four Statements:

1. Is God willing to prevent evil, but not

able?

Then he is not omnipotent.

2. Is he able to prevent evil, but not

willing?

Then he is malevolent.

3. Is he both able and willing?

Then whence cometh evil?

4. Is he neither able nor willing?

Then why call him God?

Epicurus’

Four Statements rely on three assumptions:

1. The God we

believe in is all-powerful.

2. The God we

believe in is good.

3. Evil exists

in the world.

So

the basic questions raised by the Four Statements are

If God has the will to prevent evil and the

power to do so, why is there evil?

If God doesn’t have the will or power to prevent

evil, then why is he a God?

So

what do you guys think? Which

philosopher do you agree with? Both?

Neither? Explain your reasoning.

. .

Dialogue of Ontological Argument Paraphrased from The Philosophy Book: Big Ideas Simply Explained